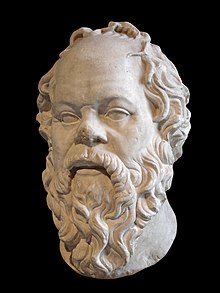

Socrates

Socrates is considered by many the founder of Western Philosophy, and was among the first moral philosophers of ethical tradition of thought.

Socrates authored no texts, but through posthumous accounts of him by many classical writers, particularly his students 3_Docs/People/Plato and Xenophon - we can form a good understanding of his approach to areas of philosophy, including epistemology and ethics. However, certain contradictory accounts of Socrates make a total reconstruction of his philosophy and character nearly impossible; this challenge is known as the Socratic problem.

In 399 B.C., he was accused of impiety, or Asebeia, and corrupting the youth. And after a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced to death and forced to drink hemlock. He spent the last day in prison among friends and followers, many of whom offered him a route to escape, which he refused. The next morning, Socrates ingested the hemlock as soon as it was prepared.

The man and his philosophy

It may come as a surprise to many that we know very little about Socrates - but seemingly, despite this, we may know him more intimately than we do of the aristocratic 3_Docs/People/Plato or the reserved and scholarly Aristotle. What we do know is that he loved to gather the young and the learned about him, luring him into some shady nook of the temple porticos, so he could ask them to define their terms.

Among this youth were rich young men like 3_Docs/People/Plato and Alcibiades, who relished his satirical analysis of Athenian democracy, there were socialites like 2_Input/2.1 Running Notes/Other/Antisthenes, who liked the master's careless poverty, and based a religion on it; and there were archists, like Aristippus, who aspired to a world in which there would be neither masters nor slaves, and all would be worrilessly free as Socrates.

Every school of thought had their representative and perhaps its origin.

How the master lived hardly anyone knew. He never worked, and took no thought of the morrow. He was not so welcome at home, since he neglected his wife and children often. Xanthippe, his wife, considered him a good-for-nothing idler who brought his family more notoriety than bread - but despite this, she loved him and could not contentedly see him die.

But why did his pupils revere him so much?

Maybe because he was much of a man as he was a philosopher. He had at great risk saved the life of Alcibiades in battle; and he could drink like a gentlemen - without fear and without excess. But no doubt they liked best in him the modesty of his wisdom: he did not claim to have wisdom, but only to seek it lovingly; he was wisdom's amateur, not its professional.

It was said that the oracle at Delphi had pronounced him the wisest of the Greeks; and he had interpreted his as an approval of the agnosticism which was the starting point of his philosophy.

Socrates saw this declaration by the oracle as a paradox, and began using the Socratic method to answer his conundrum.

Others like Diogenes Laertius, credit Protagoras for inventing the "Socratic" method.

Philosophy begins when one learns to doubt - particularly to doubt one's cherished beliefs, one's dogmas and one's axioms. Who knows how these cherished beliefs become certainties with us, and whether some secret wish did not furtively beget them, clothing desire in the dress of thought? There is no real philosophy until the mind turns around and examines itself.[1]

The Pre-Socratics

The term "Pre-Socratic" was coined in the 19th century; and was first used by German Philosopher J.A. Eberhard as "vorsokratische Philosophie" in the late 18th century.[2] It refers to ancient Greek philosophers who were predecessors or contemporaries of Socrates. The term was coined to highlight a fundamental change in philosophical inquiries between the philosophers who lived before Socrates, who were interested in the structure of nature and the cosmos, and Socrates and his successors, who were mostly interested in ethics and politics.

There had been other philosophers that came before Socrates; like the Milesians: Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, and certain Ionian philosophers like Xenophanes, Heraclitus, Pythagoras. But while many of them, the "Pre-Socratics," sought to understand the nature of external things, and the laws and constituents of the material and measurable world, Socrates, instead, sought an "infinitely worthier subject" - the mind of man.

What is man, and what can he become?

Socrates went about prying into the human soul, uncovering assumptions and questioning certainties. What do you mean by these abstract words with which you so easily settle the problems of life and death? What do you mean by honor, virtue, morality, patriotism? What do you mean by yourself?

It was such moral and psychological questions that Socrates loved to deal. Some who suffered from this "Socratic method," this demand for accurate definitions, clear thinking, and exact analysis, objected that he asked more questions than he gave answers - leaving men more confused than before. Nevertheless he bequeathed to philosophy two very definite answers to two of our most difficult problems - What is the meaning of virtue? And what is the best state? And it was his reply to these questions that gave Socrates both death and immortality.